The „homeland“ is hip again! Set the table with Rosenthal tableware, place yourself in the cantilever chair an take a good gulp of the splendid Dallmayr Prodomo coffee, because: 30 years after the fall of Berlin’s wall the cultural industry invites for a festival week to celebrate the peaceful revolution — and commands partying, remembering, debating and participation. While the capital is turned into a jolly open-air exhibition and event space, the Galerie Anton Janizewski announces a different kind of spectacle: the funeral of the Bonn republic.

Nicholas Warburg, Titelbild 1, Photo by E. G. Powell

WORDS: ALEXANDRA LANGE AND LYNN TAKEO MUSIOL

PHOTOS: E. G. POWELL, BELA FELDBERG AND SASCHA HERRMANN

Bonn republic? Yes, we almost forgot. The old Federal Republic’s aura behaves like the TV show Wetten, dass…? does towards its former host, Thomas Gottschalk: persistent but somewhat ashamed, since what it cemented in its core was a principle of carelessness: “In the Karstadt cafe the world was okey / I was young, I had goals, not only two but many” summarises the band Die Chefdenker. The Rhineland capitalism promised prosperity and security — that was until the movement of 68 rebelled against the republic’s fug (“Under the gown / Is the musty odour of a thousand years“) and the green party hammered ecological utopianism into the Bundestag. “The slander that the private circles of the high society hurl at the ones with ‚shaggy hair‘ and especially at those of female gender, adds to the observation of democratic immaturity and additional dimension of obnoxiousness. Implied is always the same: They don’t belong to us”, writes Der Spiegel in 1984.

Nicholas Warburg, BRDigung, Photo by Bela Feldberg

Still dazed from the spectacular program announcement and its show at the Brandenburg Gate including the techno legend WestBam, we enter Goethestraße 69. The only thing that greets us is a plastic funeral wreath with a black, red and golden ribbon reading: Nicholas Warburg – BRDigung. None other than Nicholas Warburg, founding member of the myth enshrouded Frankfurter Hauptschule, conjures the end of the federal republic right at the anniversary of the so called “Wende”. Warburg, born in 1992 in Frankfurt am Main, brings a touch of cozy club atmosphere into the well-lit white cube of the Anton Janizewski Gallery — including a prime view onto beautiful Charlottenburg. One could even think that Petra Todtmann invites into the Fürther Stadtmuseum under the slogan “Touch, Engage, Listen – The Federal Republic: A journey of a century”. Warburg expresses his joyous play with the republic’s insignia in Kippi, a piece consisting of draped wooden blocks in the Republic’s national colours, positioned on the threshold between the lobby and the exhibition space. A homage to the unforgotten and in Berlin’s cultural milieu still beloved enfant terrible Martin Kippenberger. Small blocks next to small blacks on a freshly polished herringbone parquet. To the best of my ability, I can see no swastika — so can’t we.

Warburg’s Germany diorama Tellerbord 2 includes the label of the popular beer brand Bitburger, hinting at the so called Bitburg controversy: In 1985 chancellor Helmut Kohl and Ronald Reagan participated in a wreath-laying ceremony at the Bergen-Belsen memorial as well as at the military cemetery of Bitburg. The latter is also the last resting place of German Wehrmacht soldiers and members of the SS. We imagine Warburg in the walnut veneered pub of the local club house at Hürth-Kalscheuren: “I’d like a beer with that – Bitte ein Bit!”

The arranged artefacts function simultaneously as connecting lines as well as ruptures between Germany’s present and the past. Rustic oak interior equally determines Warburgs narrative of West Germany as does white men circling. From the republic’s emblematic figures like Helmut Kohl and Rainer Werner Fassbinder all the way to Jürgen Möllemann — a patriarchal force presses into the room. “Crucial is, what comes out in the back”, said Kohl, paraphrasing his style of government in 1984. Möllemann’s death came from above. Warburg commemorates him softly with a rug depicting his face.

Nicholas Warburg, Die normative Kraft des Faktischen, Photo by Sascha_Herrmann

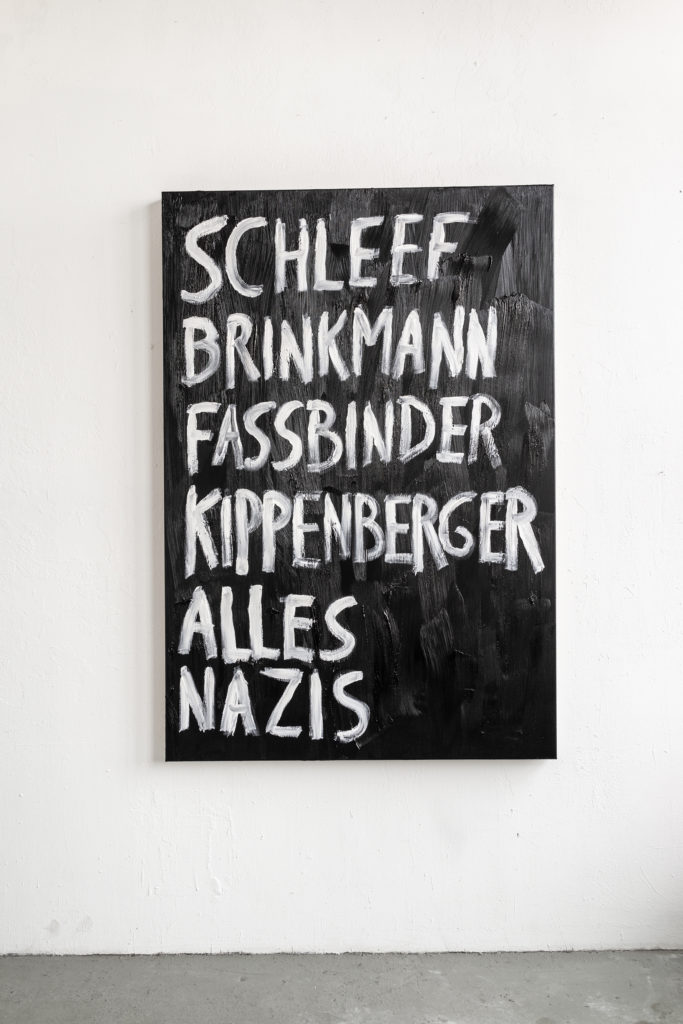

In any case: BRDigung exposes in an associative manner the conventionalism of a conservative topos, that not only contains the success story of the federal republic after the “zero hour” but also the “magnificent reunification” of the 1990s. Therefor it comes as no surprise, that Warburg shows, on a wooden panel, the conspiracy theory of the BRD-GmbH [FRG-Corporation]. Although not as charming as Dennis Mascarena in his Die Mondverschwörung, the mind map deciphers the Federal Republic as a good-for-nothing, who’s political past is as sticky as the gummies produced by Haribo. What we are dealing with here, is nothing less than the order of things, which not only constitutes a particular narrative, but an order that appropriates and reshapes history. This entails the exclusion of the erratics and the vigilants. Consequently, BRDigung reads the federal republic as an ideological system with an intrinsic reference to an opposed other. This counterpoint can be the GDR, but it also — if one doesn’t constrict dissent to moral categories of good and bad — can be the refusal to endure contradictions. Hence Warburgs interest in the ambivalence of artists such as Fassbinder, Schleef or Brinkmann, which he, in a furious scene, markes with “all Nazis“ (Titelbild 1). We are here dealing with milieu labels, that Warburg tears off in a postmodern manner, subtracting their socially acceptable truth.

Nicholas Warburg, Die Arbeit, Photo by Bela Feldberg

Warburgs BRDigung does not show the dissolution of an utopia. It reenacts the tale of West Germany by deconstructing and reassembling it. The Federal Republic’s historiography cultivated the motive of the cavity, in which every fragility of the success story was spiffed up with the ignorance of political realism — especially in the post 89 years. Only one of many examples is the initiation of a memorial for former chancellor Kohl (who played a significant role in the un-social dismantling of the GDR and its integration into the West) which was strategically placed immediately before a highly charged election in East Germany in summer 2019.

Nicholas Warburg, Tellerbord 1 (Das erkläre ich später, was ich damit meine), Photo by E. G. Powell

The demystification of the Federal Republic and its protagonists ultimately leads to a question about the conditions for an alternative writing of its history. Or put differently: what are the foundations for acting in solidarity? Reflecting on BRDigung, one can only think about the concept of homeland through the gaps in the conservative topoi. Therefore it isn’t far-fetched to ask about the breaking points of left struggles for emancipation and self-determination in a tumbling sea of black, red and golden flags before 89. Because if the Federal Republic had been a collaboration in solidarity (= a success story), we would have been able to circumscribe the state as that, which it de-facto is not: a post-identitarian moment.

But one can also witness: the German cultural scene is in a state of ecstasy. Vast sums of public funds are pumped into reenactments of the peaceful revolution, museums have a new pet subject (hurray, the East Germans!) and the radio airs a myriad of special reports on German history from an East German perspective. One can only hope that these necessary efforts are critical, multi-perspectival and sustainable. Warburg, on his part, takes advantage of the moment and shacks up our collective memory. And he doesn’t need a show at Brandenburg Gate to do that.

Nicholas Warburg: BRDigung is on view until November 12 at Galerie Anton Janizewski, Goethestraße 69, 10625 Berlin

Closing Event with Live Act + Music Video Release “September”: Der Täubling / Frankfurter Hauptschule / VHS Positiv

Tuesday, November 12, 7 – 10 pm

Visitez:

www.antonjanizewski.com/portfolio/nicholas-warburg-brdigung